Learning from Bus Buddhists

In psychological terms, context is almost everything. Much as we like to think that we know how we will act and react in a given situation, without the richness of...

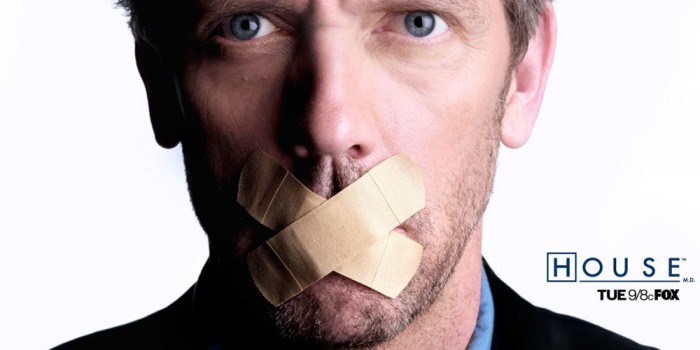

What House MD Wants Us to Know About Consumer Research

“I don’t ask why patients lie, I just assume they all do.”

Gregory House (MD)

I’m a big fan of the Fox Television series House. There’s something about the way that Hugh Laurie’s character navigates his way through life that is as appealing as it’s unattractive. Perhaps it’s that for him wisdom is the panacea for life’s anguish, not wealth or love, although of course House himself appears as driven as people fixated on the more traditional goals.

Or perhaps it’s that he has the sort of self-confidence and personal conviction that we’d all like to possess, and through watching him we can have a taste of how that might feel.

I know that one thing I do share with this TV character is his firm belief that people don’t tell the truth. As someone who’s watched and interviewed more consumers than most people, it’s usual that there’s a wide gap between what people do and what they tell me. As House says, “I’ve found that when you want to know the truth about someone that someone is probably the last person you should ask.”

Is this unfounded cynicism or healthy scepticism?

Well, lots of research exists that shows that our perceptions of ourselves are distorted; people think that they’re better looking, better driving and better thinking than average – mathematically speaking we can’t all be right (but since you’re reading this you can take it from me, you’re lovely and smart). But is this a conscious action on the part of the fibber concerned, or does it happen unconsciously?

Researchers were interested in two aspects of deception. Our desire to see ourselves as better than we really are (self-enhancement) and our capacity to say things that make us look good to those around us (impression management).

To work out whether we know we’re doing it they gave people mentally taxing things to think about (remembering an eight digit number or counting songs) whilst responding to questionnaires designed to gauge levels of self-enhancement (such as “My first impressions of people are usually right”) and impression management (“I have never dropped litter in the street”).

The results showed that impression management is largely a conscious process, lower scores were recorded when people had to think about something else, but that self-enhancement is unconscious, people do it automatically.

If you make use of or commission consumer research your mind may already be racing with ways in which this can affect research findings:

If you’re exploring an area where people might be untruthful to make themselves look better, is there a way of distracting them whilst gauging their reaction. If I’m testing a new non alcoholic drink with young men I know it may not be cool to say you like anything but lager, so I will distract them with one exercise whilst they’re drinking the new drink.

On the other hand, if you want to conduct research and self-enhancement could be a factor, asking people is the last thing you want to do. As Gregory House would say, “Everybody lies.”

And that’s a big problem. Imagine you want to get reactions to a new product. If there’s a chance that people believe that how they feel about the product says something about them – and in my experience that’s more often than not – they won’t answer honestly.

So what are you to do?

Fortunately, House knows the answer to that to, and it’s the reason that I study consumer behaviour much more than I do consumers words…

“You want to know how two chemicals interact, do you ask them?

No, they’re going to lie through their lying little chemical teeth.

Throw them in a beaker and apply heat.”

Source: Ashok K. Lalwani. The Distinct Influence of Cognitive Busyness and Need for Closure on Cultural Differences in Socially Desirable Responding. Journal of Consumer Research, 2009; 0 (0): 090114112719036 DOI:10.1086/597214