The Customer Loyalty Myth

The suggestion that customers can be loyal is odd. Think about it for a moment; who are you really loyal towards? Your family, your friends, your colleagues? Loyalty exists for...

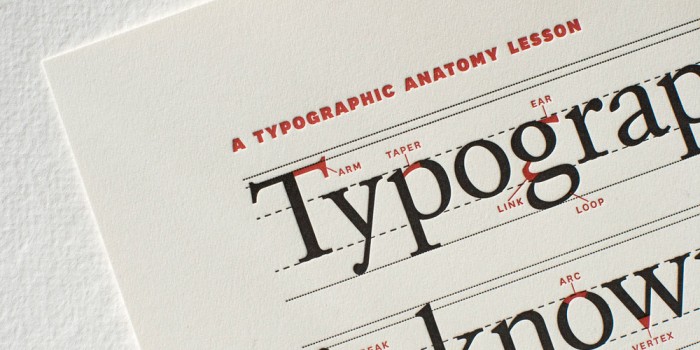

The Influence of Fonts?

|

Tell me all about it, you naughty thing. or Tell me all about it, you naughty thing. |

No one likes to feel self-conscious.

Recently I listened to interview with the actor, author, comedian and TV presenter, Stephen Fry. He was asked to sing a song called “Big John” that is essentially spoken rather than sung.

Fry has made no secret of the fact that, despite his love of music, he can’t sing a note.

As an actor, you might have thought that this task would have been well within his capabilities, but he stammered and stuttered and then stopped; “You’ve made me all self-conscious!” he declared.

There are few things more unsettling than being made self-conscious.

And yet, most market research invites the conscious mind to look in on itself; it asks the respondent to become self-conscious. It’s something we’re hopeless at. Partly because we’re unaware of how contextual elements influence the choices we make and the things we do. (And partly because we routinely decieve ourselves).

I was reading about a study that researchers from Carnegie Mellon University published recently. They compared the information people provided when they formatted the questions differently. (They tested on-line and paper questionnaires).

They didn’t change the questions; these remained the same. Instead they changed the crisp, official look and ‘serious’ font that they used in one instance for one that looked far less official and used a Comic Sans font.

Now, it’s important to say that, in my view, the experiment was somewhat compromised by a prime that they included. The researchers didn’t just change the look of the text, they also swapped the university seal for a cartoon devil.

There is a vast amount of research that shows how priming can have a dramatic impact on how people think and act, just as there is research that shows changing the legibility of writing can influence how people perceive it and react to it.

So, in this case, we don’t know exactly what is causing the effect or in what proportion.

However, what is clear from the results obtained is that the same questions presented differently elicited very different responses.

When the survey looked official and was badged with the authoritative seal of the university, respondents were far less likely to admit to having taken part in various questionable activities, like drug use and drink-driving.

What’s impossible to know is which was more accurate. Were people more willing to be honest if they thought the answers weren’t going somewhere official, or were they more inclined to claim they were engaged in risky behaviour because they felt that fitted with the ‘tone’ of the questionnaire.

What’s clear is that how a questionnaire looks changes how people answer. And that’s another problem for market research that approaches the business of understanding consumers by asking them written questions.

Whilst it wasn’t covered by this study, don’t suppose for a moment that the way in which a researcher makes a question sound, the way he or she dresses and the way the interview is recorded don’t have a similar impact: I’m aware of several studies that prove they do.

Source: Strangers on a Plane: Context-Dependent Willingness to Divulge Sensitive Information, Leslie K. John,Alessandro Acquisti, and George Loewenstein, JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH, DOI:10.1086/656423

Image courtesy: Grant Hutchinson